We drove west, towards the sea and followed the old road that young Michelangelo

rode along to watch the antique sarcophaguses at Pisa's Campo Santo. We passed

Prato and Pistoia and high above, on the foothills of the Apennine, Montecatini

Alto, the famous spa.

Pisa's foundation lies in the mists of time. Dionysius claims the town was

founded in the fourth century before the Trojan War by Greek settlers. Plinius

claims it was in the 13th century BC, Strabo said it was founded by Trojan war

Survivors. Scientists say it was either by Greek merchants or by the Etruscans

coming from the south (5th century BC).

From a Roman military colony it developed into a sea power that fought the

Byzantines and Saracens, conquered Carthage, Corsica and Palermo, Tunis and the

Balearics. Always a Ghibelline-town (protected by Friedrich I, the Staufer), it

was excommunicated by Pope Gregor IX but with the Ghibelline defeat of 1266 Pisa

sailed to a catastrophe, being defeated by the other great sea power of Genoa,

who destroyed Pisa's fleet completely (1284, Sea battle of Meloria). On the

supposed traitor - Conte Ugolino della Gherardesca - was put the whole guilt for

this defeat and they left him and his family starving in a prison.

From a Roman military colony it developed into a sea power that fought the

Byzantines and Saracens, conquered Carthage, Corsica and Palermo, Tunis and the

Balearics. Always a Ghibelline-town (protected by Friedrich I, the Staufer), it

was excommunicated by Pope Gregor IX but with the Ghibelline defeat of 1266 Pisa

sailed to a catastrophe, being defeated by the other great sea power of Genoa,

who destroyed Pisa's fleet completely (1284, Sea battle of Meloria). On the

supposed traitor - Conte Ugolino della Gherardesca - was put the whole guilt for

this defeat and they left him and his family starving in a prison.

Pisa experienced a lot of changing rulers and finally followed Florence because

the town was sold by the Duke of Milan. Only in the reign of Cosimo I de' Medici

was it getting better. He founded the university - whose most famous teacher was

Galileo -, straightened the Arno (after the plans of the late Leonardo), and built

a canal that Pisa connected with the sea again because the Arno had deposited so

much sand at its mouth that Pisa is now several kilometres afar from the sea.

The town greeted us with flocks of tourists' buses, the obligatory school

classes and a bright sky. The leaning tower had never been so white. I looked

up and imagined Galileo bending down, letting fall down a stone on a rope. By a

mishap the campanile has become a tourist world wonder. Because of the pliable

sand ground the foundation of the tower is explicitly sunk to one side.

The town greeted us with flocks of tourists' buses, the obligatory school

classes and a bright sky. The leaning tower had never been so white. I looked

up and imagined Galileo bending down, letting fall down a stone on a rope. By a

mishap the campanile has become a tourist world wonder. Because of the pliable

sand ground the foundation of the tower is explicitly sunk to one side.

The construction begun in 1173 and it must have been suspended at the completion

of the third ring, around ten years later, since a subsidence of the soil of between

30 and 40 cm. had thrown the tower out of the perpendicular, causing an initial

overhang of circa 5 cm. More than a century after the laying of the foundation

stone, building was once again begun (1275) by Giovanni di Simone, who added

three more levels, correcting the axis of the Campanile, thus the leaning tower

is less crooked than bandy.

As you know the tower is again open for visiting but this time they made the

first efforts to regulate it and to stop it from falling. Meanwhile the

architects have put so much concrete under it that it seems fairly stabile now.

In the cathedral next door it is said Galileo studied the pendulum-rules on a

chandelier. I thought it's crap because this chandelier had been installed here

long after Galileo had fallen into the hands of the inquisition and was

disbarred.

In the cathedral next door it is said Galileo studied the pendulum-rules on a

chandelier. I thought it's crap because this chandelier had been installed here

long after Galileo had fallen into the hands of the inquisition and was

disbarred.

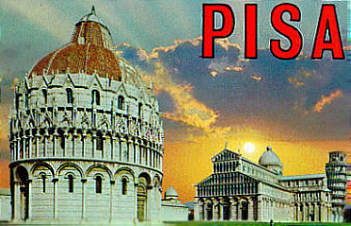

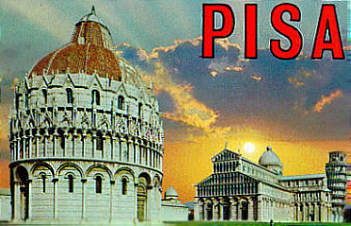

The Cathedral of Pisa is an inseparable part of marvellous four-piece ensemble

of masterpieces of architecture and art which makes the Piazza dei Miracoli what

it is. The group of buildings so scenographically set in the piazza del Duomo of

Pisa leave the visitor with an impression in part real and in part unreal, like

a fairy tale, due first and foremost to the striking contrast of the white marble

with the green grass and blue sky. In Roman times the palace of Emperor Hadrian

stood here.

In 1063, after the victory of the Pisan fleet in Palermo, Buscheto di Giovanni

Giudice was entrusted with the task of building the cathedral, which was to be

the perennial glorification of the splendour of the Maritime Republic. The money

came from the selling of the cargo from six big Saracen ships that had been captured

at Sardinia.

In the first two decades of the 17th century restorations were carried out after

a fire had gravely damaged the building (25.10.1595), destroying most of the old

interior, but the mosaic in the apse is gigantic, showing Christos Pantocrator.

The Florentine Cimabue finished this work of art, who was the teacher of Giotto.

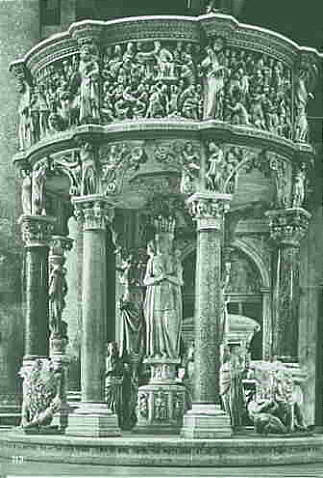

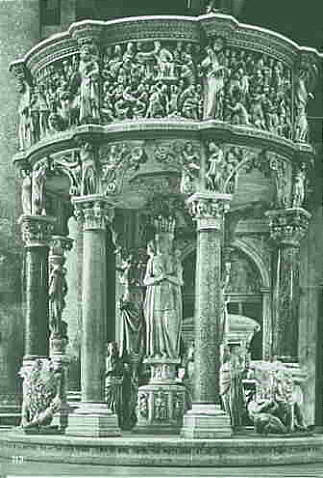

But the most interesting thing is the pulpit by Giovanni Pisano. It is a

grandiose "monster" from wood-carvings, marble and sandstone.

Nicola and his son Giovanni were both sculptors and influenced not only Giotto's

paintings but a whole generation of sculptors coming after them. Nicola was born

1220 in Apulia, his son in Pisa (thus the name, nobody knows their surname).

Giovanni travelled most likely to France and studied the Gothic cathedral

sculptures in Paris, Amiens and Reims. His last pulpit is the one of the Pisan

Cathedral. (Foto) They are four in all (two in Pisa, one in Siena and another in

Pistoia) and are either hexagonal or octagonal. The hexagon symbolize the death

of Christ on the sixth day of the week; the octagon his ascension.

The pulpits are full of symbolism like the virtues Belief, Love and Hope and the

Personification of the Arts, who are the central buttress of the pulpit. Lions,

killing deer, are the personification of the evil who are also forced (as

protection of the pillars) under the power of the church. Samson (or Hercules)

is representative of Christian Fortitude, the power. In the time of the baroque

they were dismantled and put into a dusty corner because they didn't fit the

Zeitgeist. Only at the start of the 20th century have they been put together

again but in the wrong order of the plates.

The pulpits are full of symbolism like the virtues Belief, Love and Hope and the

Personification of the Arts, who are the central buttress of the pulpit. Lions,

killing deer, are the personification of the evil who are also forced (as

protection of the pillars) under the power of the church. Samson (or Hercules)

is representative of Christian Fortitude, the power. In the time of the baroque

they were dismantled and put into a dusty corner because they didn't fit the

Zeitgeist. Only at the start of the 20th century have they been put together

again but in the wrong order of the plates.

Outside the place in front of the cathedral had filled up. At the entrance to

the round baptistery people stood in a long line. The tickets allows you to

enter this and the Campo Santo.

Outside the place in front of the cathedral had filled up. At the entrance to

the round baptistery people stood in a long line. The tickets allows you to

enter this and the Campo Santo.

In size and aspect the Baptistery is an imposing construction with a circular

ground plan and is, together with the Cathedral, the Tower and the Camposanto

Monumentale, one of the local points of the Piazza dei Miracoli. Construction

was begun in 1152 by Diotisalvi in Romanesque style. It was continued about a

century later by Nicola Pisano who added the airy loggia with its Gothic

embroidery of triangles and aediculas, the setting for sculpture from the

workshop of Nicola and Giovanni Pisano. The finishing touch to this marble gem

is the dome, terminated in the 14th century, covered with tiles and lead plaques

and crowned by a bronze figure of John the Baptist, attributed to the

14th-century artist Turino di Sano.

I liked the baptismal font despite the modern, iron Baptist upon the lock. And

even here there is one of the four famous Pisano-pulpits. This one was made by

father Nicola. How much Pisa's inhabitants appreciated this work is illustrated

by the order of the town in 1303: An armed guard had been found to protect the

pulpit against - even those times feared - vandalism.

We shared the round with an Italian tourist party. Suddenly an employee in fine

clothes and tie, stepped upon the topmost step of the basin and started to sing

several tones; the scale up and down. Despite the different tones they united to

one under the top of the egg shaped cupola. The sound was hovering under the

roof and we looked instinctively up as if it would be visible. Breathless

silence. A last three-sound (or three-tone) melting to one. Then he bowed and

vanished. Amazing show.

Across the wonderful green lawn to the entrance of the Holy Cemetery (Camposanto). It's a monumental building over whose area crusaders once scattered earth from Jerusalem's Golgotha-hill brought in 1203 on twelve Pisan galleys. (Foto) The broad ways (sort of a cloister) are filled with antique sarcophagus and steles. From the walls hang heavy anchor-chains from a time where Pisa belonged as well as Amalfi, Genoa and Venice to the four mighty sea republics. Remnants of old bright freschi cover parts of the walls. Many painters were involved, famous ones from Florence and the unknown Master of the "Trionfo della Morte" (dated about the year of the Great Plague in 1348).

I looked down and read the grave plates. My feet hesitated for one moment: I had

just stepped over the grave of Nicola and Giovanni Pisano...

The story belonging to the freschi is shameful. It's the 27th of July in 1944.

Noise of an airplane sounds over the bright, meters-high walls. It's coming

closer and closer and they fly low. Very low. And then there's the explosions.

The leaning tower is still standing but the bomb has hit the lead-roof of the

cemetery. The metal melts instantly and runs down over the wonderful old

freschi, covering the walls. What wasn't broken away from the shock waves and

lies crumbled to the ground, is glued together. Some say it was a German bomber,

but perhaps a British. It doesn't matter in the end.

The extent of the catastrophe you understand when you visit the museum attached.

There they have sorted out each tiny part of freschi in a year long work. They

have glued them together, stretched it upon wooden frames and nailed them on the

walls. Grey parts showed that those parts are destroyed for ever. I couldn't

take my eyes off it: one meter's high pictures is told the old testament. The

creation of the world and of paradise. The apocalypse, purgatory and hell. The

triumph of death: A half devil - half woman with a scythe lusting after human's

life. In the Hell's Slough of the Damned everybody is even: clergy and laymen,

noble people and the poor - everybody is taken by death. The depiction of the

corpses of three kings in various stages of decay. The fantasy and attention to

detail of those painters is amazing, enough to give you nightmares.

The extent of the catastrophe you understand when you visit the museum attached.

There they have sorted out each tiny part of freschi in a year long work. They

have glued them together, stretched it upon wooden frames and nailed them on the

walls. Grey parts showed that those parts are destroyed for ever. I couldn't

take my eyes off it: one meter's high pictures is told the old testament. The

creation of the world and of paradise. The apocalypse, purgatory and hell. The

triumph of death: A half devil - half woman with a scythe lusting after human's

life. In the Hell's Slough of the Damned everybody is even: clergy and laymen,

noble people and the poor - everybody is taken by death. The depiction of the

corpses of three kings in various stages of decay. The fantasy and attention to

detail of those painters is amazing, enough to give you nightmares.

A good photo documentation gives an idea of the original brightness of the

freschi and the terrible loss of them.

A lunch break in Pisa can be a little annoying because there's no restaurant

that isn't full and along the whole of the piazza there is no bench, nor chair

for a rest. Just a large line of market stalls selling their garbage to the

tourists.... We didn't bother to visit the centre of the town but drove on to

Lucca.

From a Roman military colony it developed into a sea power that fought the

Byzantines and Saracens, conquered Carthage, Corsica and Palermo, Tunis and the

Balearics. Always a Ghibelline-town (protected by Friedrich I, the Staufer), it

was excommunicated by Pope Gregor IX but with the Ghibelline defeat of 1266 Pisa

sailed to a catastrophe, being defeated by the other great sea power of Genoa,

who destroyed Pisa's fleet completely (1284, Sea battle of Meloria). On the

supposed traitor - Conte Ugolino della Gherardesca - was put the whole guilt for

this defeat and they left him and his family starving in a prison.

From a Roman military colony it developed into a sea power that fought the

Byzantines and Saracens, conquered Carthage, Corsica and Palermo, Tunis and the

Balearics. Always a Ghibelline-town (protected by Friedrich I, the Staufer), it

was excommunicated by Pope Gregor IX but with the Ghibelline defeat of 1266 Pisa

sailed to a catastrophe, being defeated by the other great sea power of Genoa,

who destroyed Pisa's fleet completely (1284, Sea battle of Meloria). On the

supposed traitor - Conte Ugolino della Gherardesca - was put the whole guilt for

this defeat and they left him and his family starving in a prison.

The town greeted us with flocks of tourists' buses, the obligatory school

classes and a bright sky. The leaning tower had never been so white. I looked

up and imagined Galileo bending down, letting fall down a stone on a rope. By a

mishap the campanile has become a tourist world wonder. Because of the pliable

sand ground the foundation of the tower is explicitly sunk to one side.

The town greeted us with flocks of tourists' buses, the obligatory school

classes and a bright sky. The leaning tower had never been so white. I looked

up and imagined Galileo bending down, letting fall down a stone on a rope. By a

mishap the campanile has become a tourist world wonder. Because of the pliable

sand ground the foundation of the tower is explicitly sunk to one side.

In the cathedral next door it is said Galileo studied the pendulum-rules on a

chandelier. I thought it's crap because this chandelier had been installed here

long after Galileo had fallen into the hands of the inquisition and was

disbarred.

In the cathedral next door it is said Galileo studied the pendulum-rules on a

chandelier. I thought it's crap because this chandelier had been installed here

long after Galileo had fallen into the hands of the inquisition and was

disbarred.

The pulpits are full of symbolism like the virtues Belief, Love and Hope and the

Personification of the Arts, who are the central buttress of the pulpit. Lions,

killing deer, are the personification of the evil who are also forced (as

protection of the pillars) under the power of the church. Samson (or Hercules)

is representative of Christian Fortitude, the power. In the time of the baroque

they were dismantled and put into a dusty corner because they didn't fit the

Zeitgeist. Only at the start of the 20th century have they been put together

again but in the wrong order of the plates.

The pulpits are full of symbolism like the virtues Belief, Love and Hope and the

Personification of the Arts, who are the central buttress of the pulpit. Lions,

killing deer, are the personification of the evil who are also forced (as

protection of the pillars) under the power of the church. Samson (or Hercules)

is representative of Christian Fortitude, the power. In the time of the baroque

they were dismantled and put into a dusty corner because they didn't fit the

Zeitgeist. Only at the start of the 20th century have they been put together

again but in the wrong order of the plates.

Outside the place in front of the cathedral had filled up. At the entrance to

the round baptistery people stood in a long line. The tickets allows you to

enter this and the Campo Santo.

Outside the place in front of the cathedral had filled up. At the entrance to

the round baptistery people stood in a long line. The tickets allows you to

enter this and the Campo Santo.

The extent of the catastrophe you understand when you visit the museum attached.

There they have sorted out each tiny part of freschi in a year long work. They

have glued them together, stretched it upon wooden frames and nailed them on the

walls. Grey parts showed that those parts are destroyed for ever. I couldn't

take my eyes off it: one meter's high pictures is told the old testament. The

creation of the world and of paradise. The apocalypse, purgatory and hell. The

triumph of death: A half devil - half woman with a scythe lusting after human's

life. In the Hell's Slough of the Damned everybody is even: clergy and laymen,

noble people and the poor - everybody is taken by death. The depiction of the

corpses of three kings in various stages of decay. The fantasy and attention to

detail of those painters is amazing, enough to give you nightmares.

The extent of the catastrophe you understand when you visit the museum attached.

There they have sorted out each tiny part of freschi in a year long work. They

have glued them together, stretched it upon wooden frames and nailed them on the

walls. Grey parts showed that those parts are destroyed for ever. I couldn't

take my eyes off it: one meter's high pictures is told the old testament. The

creation of the world and of paradise. The apocalypse, purgatory and hell. The

triumph of death: A half devil - half woman with a scythe lusting after human's

life. In the Hell's Slough of the Damned everybody is even: clergy and laymen,

noble people and the poor - everybody is taken by death. The depiction of the

corpses of three kings in various stages of decay. The fantasy and attention to

detail of those painters is amazing, enough to give you nightmares.