The visit to the Uffici was on our agenda but I will spare you

the description of it. You know what's in it: paintings, paintings,

paintings. But it should in no way be missed and you should be

armed with a good guide to learn the meaning of the large Botticellis

for instance.

A visit of the church of San Miniato is an exceptional event we

devote ourselves the next morning. You have to cross the Arno and

climb the steep way up to Piazzale Michelangelo, the outlook and

parking space for cars and buses, decorated with another copy of

David. You can have a Cappuccino in an airy cafe with noisy kids

playing computer games.

A few steps further we were on the Cross-Mountain. Some more

steps up and we passed San Salvatore. This small, brown Fransiscan

church was Michelangelo's favourite church but it is locked. We

had a break in a small park, meadows where families were having

picnics, sitting on a bench in the shade and enjoying the silence.

Down there the street noise is seething but here it's peaceful. A

monk was passing by. We followed until we stood in front of another

steep flight of stairs. High above throned San Miniato. There's

the legend that the beheaded martyr Minias (he suffered under

emperor Decius in 250 A.D.) had picked up his head and ran with

it up this steep hill (without the steps then). On the place

where he fell down dead was erected this church (finished about

1207). I admired the ancient thick Carrrara-marble plates with

intarsias of dark green serpentine of the facade, which was the

model for the baptistery for instance. High above the eagle of

the guild of Calimala perches, in its claws he has a bundle of

wool.

Inside you'd be startled by the darkness, but it's worthwhile to

have a look at the precious interior. It's lonely and quiet, but

outside of the church's coolness the sun glistened, flooding the

terrace. Tourists stood, looked and photographed the town beneath.

But we searched for the entrance to the cemetery.

Do you know Italian's cemeteries? It's a stone-desert, sorrow

turned to stone. Fascinating. Monumental steles, crosses, vases,

chiselled from stark white marble. The street is lined with family

chapels like a procession. You can enter them all, there are long

walls with coffins looking like drawers. Outside more bronze busts,

sad puttos and angels, ivy- and laurel garlands around pillars. It

seemed to be endless. But then I saw it: The death angel - a naked

Thanatos, his torch fallen to the ground, full of grief overthrown

a gravehill, his face burried into earth. I stood in awe for this

I've never seen before.

Behind the church still stands the brown clock tower. I told you

already about the fall of the republic of Florence in 1530. This

clock tower was an exponential aim for emperor Charles V, who stood

in front of Florence' gates just two years after his Sacco di Roma.

Michelangelo, just busy to work on San Lorenzo's New Sacristy,

joined the committee to protect the town. He erected the town walls

(still to be seen from here) around the hills, the town and down the

valley. And he had the idea to protect the clock tower with

matresses,

with straw- and wool bales. It worked out for the cannon balls

bounced off and fell to the ground without leaving damage. But

it didn't help, after eight months the town was starving. There

was food for just three days. The citizens considered seriously

to burn down their town, kill children and women and to destroy

themselves in an inferno before it would fall into the enemy's hand.

Finally Malatesta Bagliori - the hired condottiere of Perugia and

commander of Florence troops - betrayed the town, united with the

Spanish troops and opened the gates for Charles' army. The town

capitulated. He appointed the Medici-bastard Alessandro as sovereign

and gave him his daughter Margherita. Alessandro was the most hatred

Medici ever. He led a reign of terror. But the man behind them

was Baccio Valori, the governor, while Alessandro was just a puppet

in his hands. The execution starts, Michelangelo's friends are the first.

Even he was on Valori's list to be executed for he was under the

rebels.

The prior of San Lorenzo hid him in the clock tower of San

Niccolo where he spent several month in constant fear until

pope Clement VII intervened (perhaps I have to add here that

Clement fully accepted the fall of Florence and was even involved.

After all he straightened the way for his family to take control

again for Alessandro was his son). Clement wanted his friend back

for Michelangelo had to finish his work in

San Lorenzo, and so he was saved. A few months later he had to made

a work of art for Baccio Valori, the willing servant of the Pope and

the murderer of his friends. What could he do? It is the Apollino,

to be seen in the Palazzo Vecchio.

Alessandro himself was murdered soon by one of his relatives

Lorenzino.

It is Sunday. What to see? There's so much a year wouldn't

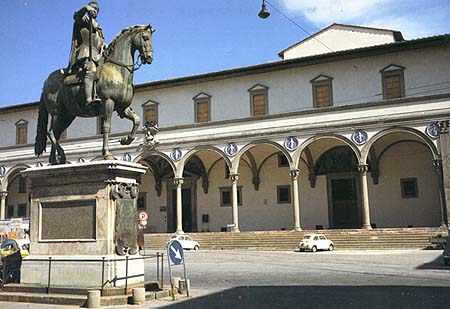

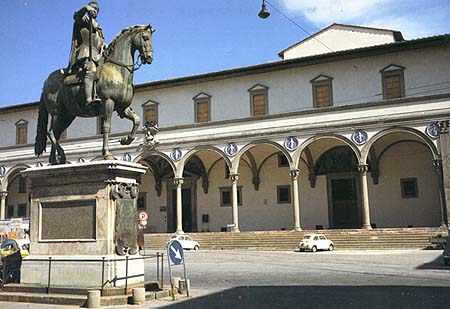

be enough. Through the empty streets our way leds to Piazza Santissima

Annunziata. A place that belongs to the most beautiful in Florence

because of its ensemble of buildings. First there's Brunelleschi's

foundling house, a grey-white loggia with terracotta-medaillons,

two green, bizarre fountains and an equestrian statue of Duke

Francesco.

In the square took place a flower market. Geraniums over geraniums

and women standing

in long rows. It's Mother's Day, but what happens

here? And why do the women carry the flower pots into the church?

We follow them into the church Santissima Annunziata, passing the

covered cloister of the votive gifts. For hundreds of years pilgrims

have left their gifts here until they burst the room and they were

removed. But we are curious where the women are carrying their

flower pots.

Baroque splendour meets us: grey, white and gold. The women set

up the pots in front of the

miraculous image of Virgin Mary. Of

course! It hangs in a gigantic tabernacle. So big the tabernacle,

so little the painting. The Madonna wears a real crown and a golden

necklace. We are dazzled. The altar gleams with pure silver, a

trellis of tied bronze ropes. From the ceiling hang countless burning

bronze lamps. Thick marble pillars surround it. According to the

inscription it cost 4.000 Florin, which was an enormous sum. The

place isn't big enough for all those red flower pots. The women

kneel in front of the trellis and pray ardently.

We came at a not very suitable time for the church is filling

for a mass. The servers are ringing already. Like everybody we

stand in front of the benches and listen to the priest's words.

He's preaching the paternoster I guess and the crowd answers. A

simple woman behind me prays loudly. We better go out. Somehow we

feel like intruders.

The door to the famous 'cloister of the dead' is locked, like

the entrance to the museum of San Marco. But if you've read my

story 'San Marco', you know this already. It is really a pity

for the former monastery is really worth a visit. There are the

touching freschi by Fra Angelico with which he painted the rooms

of his brothers. But the church is open and there happens what

I described in my story - well, not really. But I spoke to

Savonarola's monument half-aloud and had the feeling that he

was piercing my eyes.

There's still time to visit the Bargello, a communal palace

built in 1250, later the place of the podesta (mayor). Even

later then the police captain had his domicile here. It has a

lovely yard (Foto) and a steps that leads to a great museum.

From 1502 on this yard was the execution place. The gallows

was right beside the well. There's Giambologna's Flying Mercury

to admire, the gleaming bronze cast of a fragile, dancing God,

hovering in the air. And there's Michelangelo's

Drunken Bacchus .

He chiselled him in Rome where he fled after Lorenzo's death

and the banning of the Medici. Back in Florence he had made a

Cupid he sold as antique putto to a cardinal in Rome. It was

the only trick he ever played, so he is forgiven. Of course the

cardinal found out but wasn't mad at him. Instead he gave him

work and for his patron Jacopo Galli he made then the Drunken

Bacchus, unsteady in his movements, the flesh soft and delicate,

the facial expression tipsy. With this he overcame the 'dry,

hard and sharp edged manner' of the middle ages as Vasari wrote.

Also there's his Tondo Pitti and the marble bust of Brutus

(Foto). According to Vasari it glorified Lorenzino de' Medici,

the acclaimed Florentine patriot who killed the tyrant Alessandro.

Murderers of tyrants are heroes? Well, perhaps....

More?