Dante above all, who was banned as victim of this party-quarrel, accompanies us to his quarter between Via del Corso and Piazza Signoria. His family, the Aligheri, owned some houses here. In the small church of San Martino he married Gemma Donati. The house of Beatrice Portinari - his immortal Beatrice - stood on the Corso, now Palazzo Salviati. When you enter this house to change money, a statue remembers you that Cosimo I spent his youth here...

In this town of history I'm feeling often more familiar than in present times.

But for now there’s the church Santa Croce by sunset. The people say if

you want a photograph you have to go at sunset. Otherwise the sun is

behind it and you will never get a picture of it. The people are right.

A deep blue sky is beaming over the wide place - simply azzurro. On

two days in summer the Florentine youths are playing a sort of football

here in old costumes of the middle ages. It’s a pretty rough and brutal

sport but they still like it. The church stands at the end of

this place. The setting sun hits the white marble, the green serpentine

and red porphyry; the doves, teens and tourists are having it for

themselves and the Florentines meet for a chat.

Santa Croce has traditionally always been used for important civic and

religious events because it is large enough to contain crowds of people.

This is where the Franciscan preachers, as well as St. Bernardino of

Siena, during the plague of 1437, addressed the population. This was

also where Carnival and May Day festivities were celebrated, as well

as tournaments, jousting and carousels, especially during the

Renaissance, with the enthusiastic partecipation of the younger

members of the Florentine aristocracy: such events included the

famous jousts described by Pulci (1469) and Poliziano (1475), with

Lorenzo and Giuliano de' Medici among the principal protagonists.

The Basilica of Santa Croce dominates the entire square. Constructed

between 1295 and 1443 on the site of an earlier and smaller Franciscan

oratory, built in around 1225-26, when the Saint was still alive, it

was subsequently enlarged in 1252. Arnolfo di Cambio, the brilliant

head architect of the City Council was entrusted with the new project

and, almost immediately afterwards, the city also commissioned him

to construct the new Cathedral and Palazzo della Signoria.

On the left side from the church Dante Alighieri is looking at us

with his "Divine Comedy" in hand - a late monument for the expelled

son of the town. His family didn’t belong to the emperor-faithful

(and thus enemies of the Pope) Ghibellinis. When the tide had turned,

he had to leave the town, in absentia sentenced to death and didn’t

see his beloved Florence ever again. Well, even then the right ‘book

of party’ was necessary for survival. Today Florence sends

oil for the lamps upon his grave in Ravenna each anniversary of his death.

Inside darkness and coolness are ruling. And there’s Michelangelo’s

grave, just right from the entrance. It never looked so gigantic in

photos. Three marble personifications of "sculpture", "painting" and

"poetry" surround his sarcophagus. The three things Michelangelo

had controlled to perfection.

His friend and adorer Giorgio Vasari did his job well to regard highly

the greatest of great artists. Vasari - also his biographer - not only

knew him very well, he loved him and - because he was artist

himself - he understood him completely: Michelangelo’s terribilit`a.

He always had been a victim of his own character, his talent, his

ingeniousness. But where had he received this genius from? Perhaps

we’ll find out here.

Actually the Romans and the pope wanted to have him buried in Rome

but his nephew remembered his wish to be buried in Florence. He stole

the dead body one stormy night and rode with him upon his horse the

long way from Rome to Florence. At least so the legend goes.

We are passing the cenotaph for Leonardo, passing the graves of

Machiavelli, Rossini and Galileo Galilei. After his inquisition

trial in Rome, Galileo was placed under house arrest, but he was

at least allowed to continue his studies. After his death in 1642 Grand

Duke Ferdinando de' Medici wanted to place a monument here over his

grave. But Pope Urban VIII warned the Duke for Galileo had

stubbornly defended his thesis that was opposed to the Holy Bible.

Therefore he would take each monument for the astronomer as a

personal offence against his authority. Well... Ferdinando wasn’t

brave enough to resist the pope and so it came that the body of the greatest

scientist of his time lay unburied for almost 100

years (well, in a coffin I assume) in a cellar under the clock tower

of Santa Croce. Only in November 1992, exactly 350 years after his death,

Galileo was openly rehabilitated by Pope John Paul II.

This church has important and imposing small chapels that are like a

string of pearls. Each noble family wanted to have its own, for instance

also the Rucellai, the family of Michelangelo's mother.

Evening falls when we are in the direction of the Uffizi Gallery.

Above our heads leads the corridor of Vasari, it is a sort of secret way, that

leads from Palazzo Vecchio (the town hall) over Ponte Vecchio to

Pitti-Palace, the place of the Medici-dukes of Toscana. The Uffizi-yard

is broad and empty until it is actually besieged by tourists who

desire entrance to the museum. But there it is: under the Loggia -

Cellini’s Perseus, lifting the head of Medusa high in the air,

triumphantly, naked and bronzed. Not far away from it, naked, firm

marble buttocks are held toward us. As a gay man you have come to the

right place it seems ;-) It belongs to a group of men that raid

women from the tribe of the Sabin, an old legend that belongs to

Rome. If you want to learn more about Cellini and the excitingly

work of "Perseus", just click

here.

In front of the entrance to Palazzo Vecchio - this monstrous building

that stands tall above our heads in the warm light of lanterns - "David"

is waiting. Verdigris covered, but beautiful. And the difference between

copy and original we will see later.

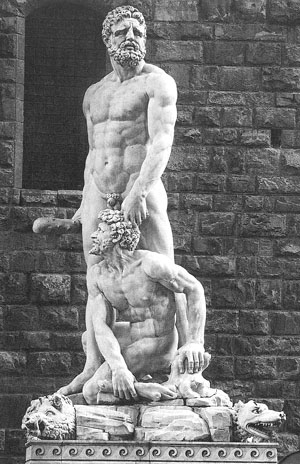

Right beside stands the ungainly figure-group by

Baccio

Bandinelli.

"Cacus and Hercules". Cacus was a gigantic, murderous monster, a son

of Vulcanus, the blacksmith God, who was fought by Hercules finally.

This group was compared to "David" as an object of surreptitious

laughing. Cellini called it a "Melon squeezer". Poor Bandinelli.

Well, it wasn t that easy for Michelangelos contemporaries. It wasn’t

easy to outdo "David". Michelangelo's flexing of muscles and proportions

of the male body were perfect. And everything that came afterwards,

was grossly exaggerated. You know, sort of "Mister Universum".

Nonetheless the citizens left the figure standing where it was:

right beside the entrance to town hall, to protect the senate and

to protect the town. And as a warning: Florence was a free state,

independent from the pope and everybody that dared to attack it would

get it like Goliath from David. Like the Jew woman Judith did with the

conquerer Holofernes, like Perseus did with Medusa....

You can enter the inner yard of the town hall without problem. There's

a cute putto-spring in the center of it made by Verrocchio - who was

the teacher of Leonardo da Vinci. Formerly the putto had spun around

himself with water power, a dolphin lovingly pressed to his cheek,

but now it doesn’t anymore. The square, supported by golden pillars

is completely decorated with frescos.

To celebrate the marriage of Francesco I de Medici with the Habsburg

princess Johanna of Austria the yard was painted with towns of the

Habsburg Reich like Prague, Passau, Graz, Freiburg, Linz, Bratislava,

Vienna, Innsbruck, Konstanz, etc. etc.

The rooms of the town hall can be visited and shouldn’t be missed.

They are mostly painted by Giorgio Vasari, but there are some fine

sculptures too, like the "Victory" by Michelangelo and some other

famous Renaissance-artists.

The most interesting tale happened there when Leonardo and Michelangelo

started a competition. In 1504 both had got the order to paint the Room of

the five hundred where the Senate of Florence (signoria) gathers. Both started

their work: Leonardo decided to portray the "Battle of Anghiari" (see picture

below), Michelangelo for the "Battle of Cascina".

Michelangelo proceeds well, but Leonardo - all self-confident fop and always up to

try out new things - tried a wax technique. For this, a fire has to be

lit to make the wax soft but since the fire was too hot on the lower side of the

fresco, the wax melted and the colours ran down, leaving long, tough traces down

and the fresco was destroyed.

Michelangelo said nothing, no triumph, no anything

although both weren’t exactly what we would call friends. Leonardo

simply went away and got busy with other things. The painting he had

forgotten instantly. And also Michelangelo never finished his fresco

because he was called to Rome to work for pope Julius II.

Careful examinations hasn't found any traces of it. Later it was Giorgio

Vasari who painted finally the room with huge freschi of battles. Of

Michelangelo's freschi there is just a cartoon left made by Aristotele da

Sangallo (1542) and is situated in Norfolk. Click here to see a sketch of

Michelangelo:

Outside again there is the large spring, the Florentine call "Biancone" -

the not beloved "big white one". It is the Neptune-fountain by

Ammannati who is similary unsuccessful like "Cacus and Hercules"

by Bandinelli. The spoiled Florentine mocked it as always.

When you cross the Piazza Signoria you reach the large shopping mall

of Florence: the Via Calzaiouli. Ragazzi and tourists are mingling,

saunter up and down, from the cathedral to town hall and vice versa.

In the night you just can guess the big dimensions of the cathedral

and in front of the baptistery people stand and admire the

"Golden Gates of Paradise" made by Lorenzo Ghiberti. There’s the

tale of Brunelleschi and his friend Donatello, both had applied for

the contest of making the doors to the baptistery. Finally Ghiberti

won. Brunelleschi and Donatello went to Rome to study there the

antique monuments and to dig the Forum Romanum (yeah, they were sort

of predecessor of Sebastian von Scheffel ;-) The uneducated Roman

seemed to both Florentines very suspect because they thought they would

dig for gold (And probably both had been seen in indecent establishments

for gay customers). Until very much later the Romans also got the idea

to dig there, what gave the push for the excavations to the antique

Forums of the emperors.

Brunelleschi arrived in Florence again just in time. The architects of

the duomo had the very difficult task of finishing the building with a

cupola. But they didn’t know how. Well, good old Brunelleschi thought

he had the solution. In presence of the signoria, the Senate of

Florence, he presented his proposal in demonstrating a standing egg.

You know, the "egg of Columbus" was actually the "egg of Brunelleschi".

He hit the egg upon the table and it stood. The model of his cupola

was daring. So daring that everybody was laughing. The space was so

big that it seemed to be impossible to close it. But Brunelleschi -

as we know - had studied Rome’s antique monuments, so the Pantheon,

which built a perfect circle in a cube. So Brunelleschi changed his

model to an egg-formed cupola that was erected within sixteen

years. It is the biggest self-carrying cupola of a Christian church.

Not even Saint Peter in Rome achieves its dimension. Remember it was

built without having cranes, without cement machines, without computer

animation or -calculation. Some scientists today are saying, the artists

of the time of the Renaissance had found the gate to macrocosm - in

their minds of course. All their thoughts are hovering in the

endless depths of the rooms. Matter can't disperse. But probably

it was just earth shaking compared to the gloomy area of the Middle

Ages.

If you need more information about the duomo I recommend reading

this.

Right beside the duomo is the bell tower of Santa Maria del Fiore, one of the most

beautiful in Italy, was an (extremely costly) invention of genius by Giotto which was

created more as a decorative monument than a functional one. In 1334 the great

artist started when work on it had already been interrupted for over

thirty years, while Arnolfo di Cambio worked for the Cathedral. Giotto

preferred to create something of his very own: the bell tower.

The artist worked from 1334 to 1337, the year of his death, on the

addition of the new architectural element that was to enrich the square, but only

lived to see the first floor of his project completed, where the pointed

entrance stands. White marble from Carrara, green marble from Prato and

red marble from Siena colour the surface (which today are the national

colours) while also dividing it up with classical rigor; a figurative

"narrative" (an indispensable form of expression for a painter) runs

around all four sides, carried out with a series of octagonal tiles

in relief by Andrea Pisano (who completed the South Doors of the

Baptistery in 1336) from designs that were carried out in part by

Giotto himself.

There are statues made by Donatello (you remember the friend of

Brunelleschi, the builder of the cupola). Formerly they stood as

decoration for the bell tower but of course they were too precious

to rot in sour rain and fumes. Once his figure of "Habakkuk" was

finished, Donatello stood in front of the very livid looking old

Prophet and cried out "Favella! Favella! Talk!!! Or the plague

should get you!"

But let me tell you something about Giotto. It started on a day in 1266.

On this day Giotto di Bondone was born. He was a shepherd's boy who

flabbergasted the old Master Cimabue while he was drawing a perfect

circle in Tuscany sand, there, out on the fields. Cimabue (who had

himself great merits as painter) gave Giotto an apprenticeship. You

know, in Giotto's time all churches were white washed, the old

freschi and mosaics removed and over painted. Why? Because the people

remembered the words of the New Testament: "You shouldn't make a

picture of myself." Well, somehow the old Greeks got bored with the

white churches and started to paint their monasteries again but

they had forgotten how to paint. When you match freschi, mosaics

and sculptures from ancient times with the time of the early middle

ages, your hair stays on end. It was as if they had been blind.

They couldn't work stone, no clue about perspective. But Giotto

sat among his sheep and drew from nature. Later he worked in

Padua, Rome, Assisi and of course Florence.

For instance he painted several chapels of Santa Croce with themes

of the life and death of Holy Francis.

Well... I don't know why he didn't have any pupils or perhaps they

had been that bad that nobody could compare with Giotto's genius.

Anyhow, again it took one hundred years before another Giotto was

born, exactly here in Florence: Tommaso di Giovanni di Simone Guidi,

called Masaccio.

He studied Giotto's freschi in Santa Croce and quickly learnt to

continue his work and even more: He was the real new man who

remembered the perspective painting. His outstanding freschi in

the Brancacci-chapel of the Carmine-church were a never ending

source for studies. Michelangelo learnt the perspective

painting there, but more about this later.

Unfortunately Masaccio - wild and gay - died an early death in Rome

only 27 years old. He hadn't had time enough but what he did was

earth shaking enough to start a new era. The time of the Rinascimento

was born, the time of the neo-antique, the time of remembering the

Greek and Roman masters.

Back to the "Biancone". In front of it there’s a porphyry plate

inserted to the ground. It tells us that exactly at this place - for

about 500 years - Savonarola was burnt to ashes. Four years before

his death he burnt his "pyre of vanities". He was the Prior of the

church and Dominican monastery of San Marco and if you want to read

his story please click

here.

The whole of Florence knew that he was dying innocent, but breathed relieved -

freed from the urge to do good things. Michelangelo didn’t say a word

about the events in Florence. Although he does share a part of Savonarola’s

opinions, he condemned his fanaticism. Michelangelo was fanatic enough

himself to know what evil it brings.

Was it fair? The Florentines are still biased. Still they bring flowers

to this place on the day of his death.

Next morning is a fine opportunity to visit the granary. That’s a

church now, called "Orsanmichele" (actually San Michele in Orto,

because there once was a nunnery with a garden). This building had in

1350 a double function of the town granary and of an oratorium.

Arnolfo di Cambio had gotten the order to built an open hall,

to protect the merchants for rain and sun. But of course they had to

hang pictures of the Holy Michael and of the Madonna, as protection

from high above so to say. Well, the picture of the Madonna started

to work miracles and soon enough pious people were gathering to sing

"laudi" to honour the "Madonna of the Gracious". A brotherhood was

building. And soon later - after a fire - the still present, new

respresentative church was built while on the lower ground the

market was still open. The arcades were closed later with elaborated

Masswork of Florentine Gothic.

The most important things are the 14 recesses on the outer façade

because they were offered by the Parte Guelfa (the party of the pope)

to all guilds of the town to place there their patron saints. And so

it came that this building is today a precious museum itself, because

each of the rich guilds in town had engaged a famous artist.

I wonder how the town manages to protect these pieces of art against

destruction by modern vandals. I cannot imagine them standing in

Berlin or any other town in Germany without being smeared with

graffiti to say the least or in the worse case being completely

destroyed. Well... more on this theme later.

You can go inside of course. There’s a fantastic tabernacle made

by Orcagna for the miracle working picture of the Madonna. On the

ceiling are still hanging the old hooks for the sacks of grain.

Back to place of the huge cathedral. Yesterday night it was the

story of the cupola, but the interior is telling other stories.

Exciting ones. Although it is cold and empty because everything

that is precious has been brought to the museum of the cathedral,

like one of Michelangelo’s last pieta for instance.

The inside of the cupola is painted with freschi by Giorgio Vasari

again. But that’s not the interesting thing. It was in 1943 when the

Jewish people had to be deported from Florence. They remembered the

canteens and sleeping places Brunelleschi once had created for the

workers, so they didn’t have to walk two hours until they were down

and two hours up to reach the ceiling each morning and evening. The

places were still there and intact. They brought the Jews up there

and nobody ever found them there.

But there’s more exciting history: On Easter Sunday 1478 there took

place the so-called Pazzi conspiracy. Lorenzi il Magnifico de’ Medici

dragged himself seriously wounded into the sacristy while his beautiful,

not less popular brother Giuliano bled to death.

There it is, the pews that are positioned in a half round in front of the

altar. Here was sitting the noble people of the town, listenening to

the Easter-Mass. Slowly the priest lifting his arms in front of the the

altar. Just that moment there's a turmoil at the entrance. A splendid

dressed group is there, burst into the duomo, their heavy boots

scratching over stone.

A cry: "Prendi, traditore!" (Take this, traitor) and everybody is

frozen to the ground. A wild crying and screaming sounds from the

chancel, spreading out in the whole cathedral and sounding up to the

high cupola.

Bernardo Bandini pushes with all his might his short sword into

Giuliano's heart from behind. The young man falls and Franceschino

de'Pazzi pounces on him. Over and over again he stabs him with his

dagger, even when he's lying already motionless to the ground.

At the same time Maffei and Bagnone attack his brother Lorenzo.

But just one of their daggers hits and causes a deep flesh wound

in the neck. Lorenzo jumps over the balustrade, pulling his sword,

fighting, seeing a good friend dying for him beside him. He flees

through the chancel, passes the altar, into the sacristy where he

barricades himself with some of his friends. Blood is dripping on

bronze and marble.

Murder in a church! That’s an inexusable outrage, that pope Sixtus

IV had tacitly sanctioned. What had happened? Actually it was

just one another of the mad family feuds that so often happens in

Italy, until now. But the family of the Medici was something special.

Lorenzo de’ Medici as their ruling leader of town did exceptional

good things for the people and the country. But you know it: envious

persons are everywhere. The noble family of the Pazzi had enough to

leave the town's government

to any peasant's offspring of the Medici. Those parvenus! Just

the blood ennobles, they are saying, not the deeds. But nonetheless

the people of Florence had idolized Lorenzo's grandfather Cosimo, like

they do with Lorenzo himself, they knew themselves greatly protected

by the family of the Medici. But on Cosimo's grandson the revenge now

was executed. The Pazzi and their adherents found an ear even in

Rome, at the highest place with Pope Sixtus IV. He approved the attack,

because then he could spread the papal power even over Florence, the

heathen town, that so stubbornly insisted on being a republic and not

to belong to the Papal States. This conspiracy stretched even over the

archbishop of Florence: Salviati. Lorenzo and his beautiful brother

Giuliano had to die. A mercenary's army of Salviati waited in front of the

gates to the town, ready to overthrow the Signoria...

Well, the conspiracy failed. Lorenzo mourned his wonderful brother and

took terrible revenge. The Pazzi family had to suffer very hard. In the

yard of the Bargello - the police building - they had a fast trial and

next morning they were hung on the window crosses openly, also archbishop

Salviati, others banished for their lifetime.

Interested in more?