Michelangelo was a Monday's child. His mother was Francesca di Neri di Miniato del Sera e di Bonda Rucellai [my, what a fine long name... Italians tend to take over the names of their fathers or mothers - or sometimes both together. Not a bad invention, considering all those Giovanni's and Lorenzo's...] In the middle of the 13th century the family Rucellai had became wealthy when one of them learnt the secret how the nice, red colour was produced in the orient.

His father, Lodovico di Lionardo Buonarroti-Simoni, descended from a high

reputable Florentine family of the Buonarroti-Simoni, but brought it

down to mediocre civil servant and they lived in noble poverty. In 1474 Lodovico had

been send as podestŕ (magistrate) into the godforsaken area between Chiusi

and Caprese. After Michelangelo was born as second child the family moved

away, back to Florence.

The elder brother Lionardo became later a Dominican monk under Savonarola in

San Marco, another three boys were born, Buonarroto, Giovanni-Simone and

Gismondo.

His father, Lodovico di Lionardo Buonarroti-Simoni, descended from a high

reputable Florentine family of the Buonarroti-Simoni, but brought it

down to mediocre civil servant and they lived in noble poverty. In 1474 Lodovico had

been send as podestŕ (magistrate) into the godforsaken area between Chiusi

and Caprese. After Michelangelo was born as second child the family moved

away, back to Florence.

The elder brother Lionardo became later a Dominican monk under Savonarola in

San Marco, another three boys were born, Buonarroto, Giovanni-Simone and

Gismondo.

Michelangelo was hardly six years old when his mother died. In Settignano he was entrusted to a nurse whose husband worked the pietra serena in a quarry. Pietra serena is the grey stone all Florentine buildings are made from. "If I should be suitable for one thing at all", Michelangelo once told Giorgio Vasari, "then it's because I was born in the good mountain's air of Your Arezzo and was suckled between the hammer and chisel of the stone masons."

From Michelangelo's letters we learn that his father was pedantic, conservative and "closed to Arts". He determined that Michelangelo, his favourite son should have it better and become a merchant. But his son has other things in mind. Against his father's wishes he joined the workshop of the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio in Florence when he was thirteen. There he met Giuliano Bugiardini and Francesco Granacci; with both he shared a long time friendship. He learnt a lot from Domenico and was even allowed to paint some day works in a chapel of the church of Santa Maria Novella. At the same time he made for fun drawings of the several tools and his Master was impressed so much that he drew Lorenzo de' Medici's attention to the talented boy. Lorenzo noticed Michelangelo's passion for the art of sculpture and so the prince took him into his palace at the Via Larga, attached him to his household where he sat with Lorenzo's own children at the same table and was taught by the same scholars.

His first work was the bust of a Faun which is lost, but received great approval not just from his teacher Bertoldo but also from Lorenzo himself. In the evening he listened to the lessons of the Neoplatonic Academy Lorenzo had founded and received a large foundation of philosophic ideas which influenced his whole life afterwards. The somewhat gloomy young man, who was often for himself and happy just to work, was nonetheless truly acclaimed by the other pupils except one: Pietro Torrigiani. Pietro was very talented himself but Michelangelo's sharp tongue hurt him probably more than his self-confidence could bear. During a visit at the Brancacci-chapel Torrigiani showed the students his sketch he had made after the Masaccio-freschi, but Michelangelo just joked about it. Torrigiano hit him in the face, breaking his nose, and Michelangelo - not then exactly a beauty - was blemished for his whole life from then on.

Torrigiani later became the victim of his wild character. He worked the wonderful monument for Henry VII in London's Westminster Abbey, worked in England, Portugal and Spain but became a victim of the Inquisition under Torquemada.

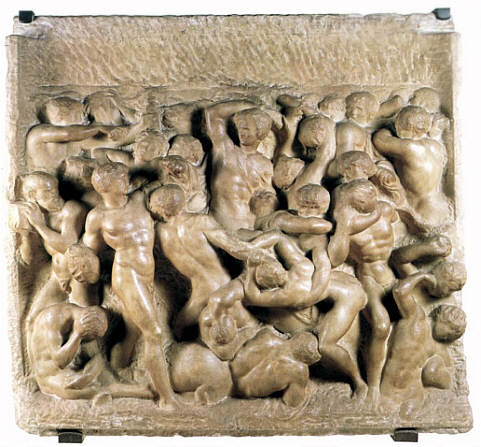

In 1491 Michelangelo chiseled for Lorenzo the "Madonna della Scala" [Madonna of the staircase]. He was sixteen years old and his conception was fairly new: In foresight of her coming fate the mighty, not moving figure directs her stare into nowhere. The small boy of Christ - in a daring back view - turns his right arm behind his back, just typical for Michelangelo, but the boy of John, the Baptist builds with his body a perfect cross, when he lounges on the railing of the steps, the coming fate of his playmate. And just a little later he had visited the Camposanto of Pisa with its antique sarcophaguses where he must have admired the relief of the story of Phaedra and Hippolytos. He used it for his "Battle of the Centaurs" - contorted, muscular, Herculean bodies. Lorenzo hung it into his bedroom.

You have read enough about Savonarola and his pious regime so I'll spare you

the details. But it was in 1492 - the Annus Mirabilis, the horrid year -

when suddenly everything changed. Why is it called Annus Mirabilis? Because

several decisive events fell together: In Italy Lorenzo de' Medici died,

Christopher Columbus detected and conquered America, and in South Spain the

Edict of Nantes (turnout) started which meant that Queen Isabella of Aragon

and her husband Ferdinando expelled all Saracens from the south of Spain

where they had happily resided and cultivated active exchanges with the

Christian world. It was a horrid year or a splendid, it depends on the point

of view. Certainly the discovery of America was a good thing, but horrid

for the natives. Surely the Spanish country wanted to have back his own land

that was occupied by the Saracens, but haven't we learnt very much from

them? When Europe persevered in ignorance and mud, the Arabs were light

years ahead. Now everything came to an end and it wasn't a good end for the

Arabs. They were either murdered or christened. Or they fled. And the death

of Lorenzo wasn't a good thing at all. Neither for Florence nor Italy in

general.Last but not least Alexander VI was the name of the new pope: Rodrigo

Borgia, the notorious, more a warrior and killer than a holy man (although

much of the tales about him are shameless exaggerated or pure invention).

You have read enough about Savonarola and his pious regime so I'll spare you

the details. But it was in 1492 - the Annus Mirabilis, the horrid year -

when suddenly everything changed. Why is it called Annus Mirabilis? Because

several decisive events fell together: In Italy Lorenzo de' Medici died,

Christopher Columbus detected and conquered America, and in South Spain the

Edict of Nantes (turnout) started which meant that Queen Isabella of Aragon

and her husband Ferdinando expelled all Saracens from the south of Spain

where they had happily resided and cultivated active exchanges with the

Christian world. It was a horrid year or a splendid, it depends on the point

of view. Certainly the discovery of America was a good thing, but horrid

for the natives. Surely the Spanish country wanted to have back his own land

that was occupied by the Saracens, but haven't we learnt very much from

them? When Europe persevered in ignorance and mud, the Arabs were light

years ahead. Now everything came to an end and it wasn't a good end for the

Arabs. They were either murdered or christened. Or they fled. And the death

of Lorenzo wasn't a good thing at all. Neither for Florence nor Italy in

general.Last but not least Alexander VI was the name of the new pope: Rodrigo

Borgia, the notorious, more a warrior and killer than a holy man (although

much of the tales about him are shameless exaggerated or pure invention).

Though Michelangelo listened to some of Savonarola's mad speeches where he damned everything: the lustful life in Florence, the forgetting of all Christian virtues, and the Pope Alexander VI Borgia above all. He accused Lorenzo de'Medici of stealing the people's money to squander it for his private joys. Which was a pure lie by the way. Michelangelo's young soul was scared when he listened in awe but then his reason won upper hand and he left. Not just the church but also his home town. He didn't feel safe after Lorenzo's death. His son, Piero, had gained ruler ship over Florence and this didn't do well. Surely everybody was expecting much from Lorenzo's son, but apparently this time the apple landed far away from the trunk.

After the incident with the troops of Charles VIII and the consequent plundering of the Palazzo Medici, Michelangelo decided it was time to leave. In 1494 he went for a short while to Venice and then to Bologna. And since his favourite motto was Heraclit's "You never step twice into the same river", each of his work will be truly unique. But one after the other.

Per incident he had found a patron and was commissioned to contribute to the grave of the Holy Dominicus which was started by Nicola Pisano. He chiseled the statues of St. Petronius, St. Proculus and the candela-bearing angel. But since there was nothing other more to do for him he wondered if he should return to Florence, which he did in Spring 1495. Perhaps in spite of the pious fanatics of Savonarola he works at the "Sleeping Cupido", a life size boy with an angel like face. A certain Jacopo Galli from Rome, looking for antique things, told him that he could sell this as antique when he would trim it old and Michelangelo agrees. Perhaps he was just afraid that Savonarola's white boys - send out to find naughty things in the houses - would destroy it. And Michelangelo was always in desperately need of money. His family was haunting him. His father didn't work properly and his brothers were much too young. So he packed one day his bag and the Cupido and followed Galli in 1496 to Rome.

The clever cardinal to whom he sold this piece of work recognized it relatively quick

as a forgery but he wasn't mad with the young Florentine but gave him work in his

palace, for instance to arrange a theatre performance. One year later it finally

happened: Michelangelo chiselled his first upright standing man, in the tradition of

Donatello whose David was the first standing and naked figure of the modern times.

(see photo). Donatello's David, wearing nothing other than a pair of

boots and a girlish hat, is full of inviting alluring ambiguity - a challenging,

coquettish boy.

The clever cardinal to whom he sold this piece of work recognized it relatively quick

as a forgery but he wasn't mad with the young Florentine but gave him work in his

palace, for instance to arrange a theatre performance. One year later it finally

happened: Michelangelo chiselled his first upright standing man, in the tradition of

Donatello whose David was the first standing and naked figure of the modern times.

(see photo). Donatello's David, wearing nothing other than a pair of

boots and a girlish hat, is full of inviting alluring ambiguity - a challenging,

coquettish boy.

Learn more about the Drunken Bacchus clicking here

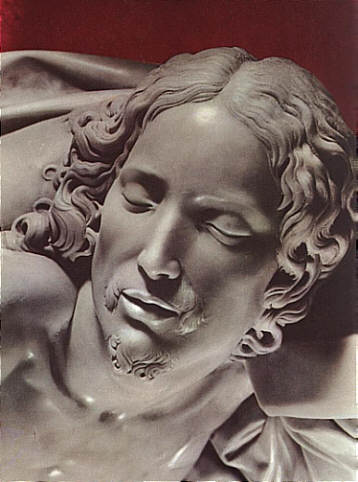

At the 27th of August 1498 was made the contract for his Pietŕ. The order was given by the French cardinal Jean de La Groslane de Villiers, the Abt of Saint-Denis and ambassador of King Charles VIII, who was ordering it for the chapel of the Kings of France in Old-St. Peter. Michelangelo is 23 years old. Three years later whole Rome was stunned by looking at this, adoring the soft lines of the marble. The gleaming shine. Jesus' peaceful, bend face. The curls. The fine formed hands. The rich drapery of Mary's skirt. And above all: She was young. Too young to be his mother. Asked about this fact, Michelangelo answered with a bible quotation: "Mother Mary, daughter of your son". He had long pondered about this sentence and came to the conclusion that we are all God's children in the end. And "innocence is not aging".

After being witnesses to a talk about the master of this work of art he crept one night into the chapel and chiselled his name into the breast band of Mary's skirt. It is the sole work he has ever signed.